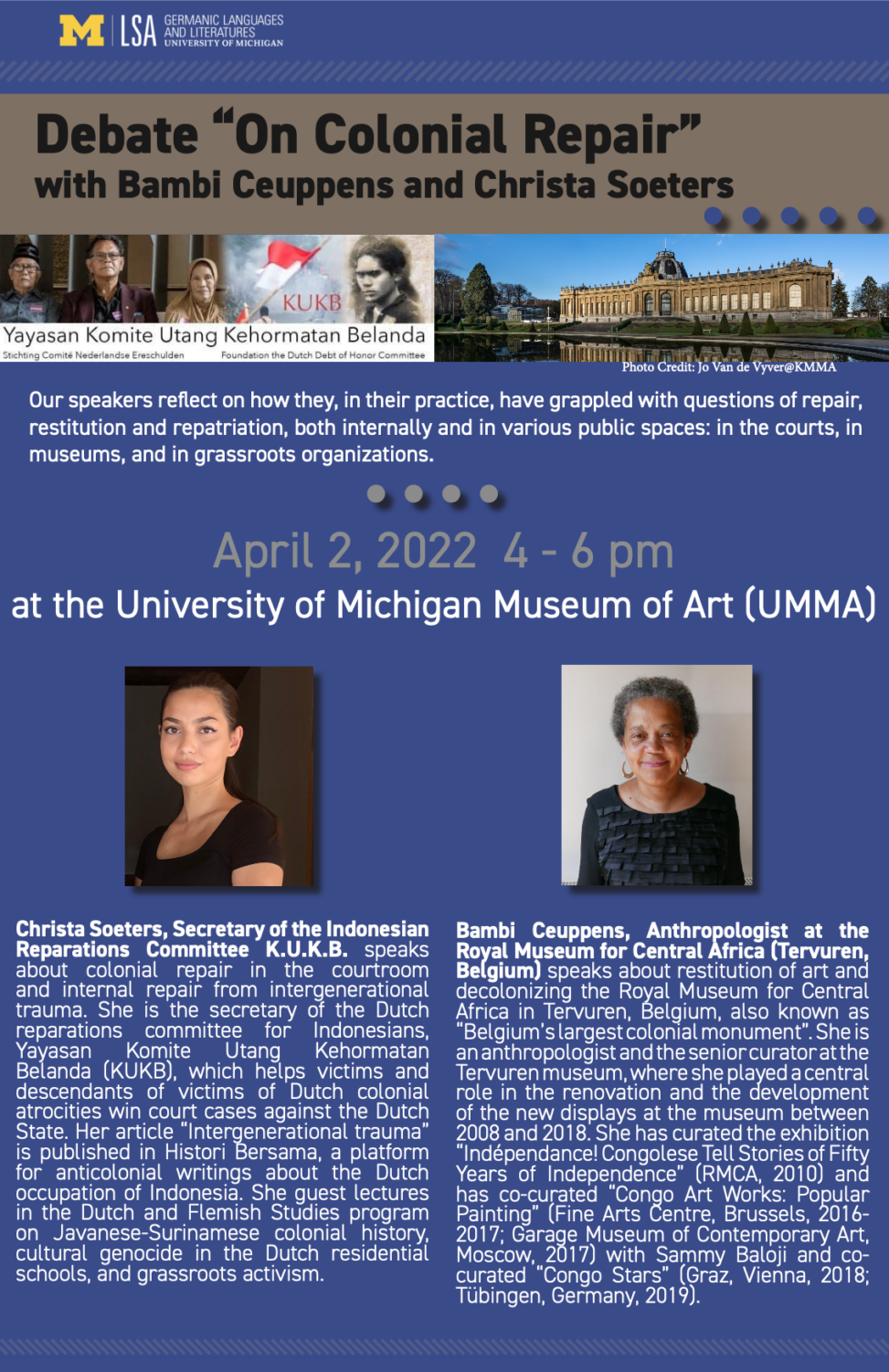

On April 2, 2022, I delivered a lecture at the University of Michigan titled On Colonial Repair. It was the first lecture I had ever given. In the Netherlands, I faced significant repression, which forced me to operate from a marginalized position, leaving me with little opportunity to gain experience in public speaking or creating presentations. I am deeply grateful for the opportunity and getting the chance at the University, despite my lack of experience, to share my knowledge on this platform—the foremost university of the United States. This lecture marks a pivotal point in my development as a speaker and teacher, though it came about in an unconventional order, as I’ve had to navigate this process in reverse.

The lecture addressed three levels of colonial repair:

- Individual Repair

How my family and I have been impacted by colonialism, and my journey to Indonesia and Suriname to seek healing. - Collective Repair

The legal battles led by the Yayasan Komite Utang Kehormatan Belanda (KUKB) against the Dutch state, representing Indonesian victims of atrocities during the independence war. - Global Repair

Colonialism is a global system, with the United States at its core. Therefore, colonial reparations must necessarily involve global reparations.

Context: The lecture begins with a discussion of a segment from De Balie, a Dutch platform that hosted a program on a book publication about how the Netherlands has covered up its war crimes in Indonesia. During this event, I attempted to ask a question, but Anne-Lot Hoek (a white woman) censored me, stating I was not allowed to speak because I had called her a racist—which, of course, is a deeply racist act in itself. The background of this incident involves a conflict between Anne-Lot Hoek and Marjolein van Pagee (another white woman) over Indonesian history. Anne-Lot Hoek subsequently contacted the employer of the chairwoman (an Indonesian woman) of Marjolein van Pagee’s foundation, attacking her professionally. I called Anne-Lot Hoek a racist for targeting Indonesian women and attempting to financially ruin someone over intellectual critique. This case demonstrates how unsafe we, as the Indonesian diaspora, are from white people when we engage with our own history.

Years later, Anne-Lot Hoek’s husband (a white man) contacted universities I collaborate with, demanding that they distance themselves from me because I had exercised my right to quote and had used a segment from this event in my lecture. This incident highlights the colonial and racist conditions in the Netherlands, where there is a severe lack of integrity, and where many colonial actors are working within so-called decolonial discourse, erasing Indigenous voices. Although the United States is itself a colony, the Dutch colonial structures that affect Suriname and Indonesia do not carry the same weight there, which provided me with an environment where I could begin to free myself from Dutch colonialism.